Those of us who work with aggressive dogs often ask our clients about their dog’s physical health. Have they been to the vet? Are they showing any signs of illness or pain, perhaps, stiffness in the joints? This is because, physical discomfort often causes aggressive behavior in dogs. I’ve always thought about it like this: When animals are physically uncomfortable, their capacity for dealing with unpleasant emotions is significantly decreased.

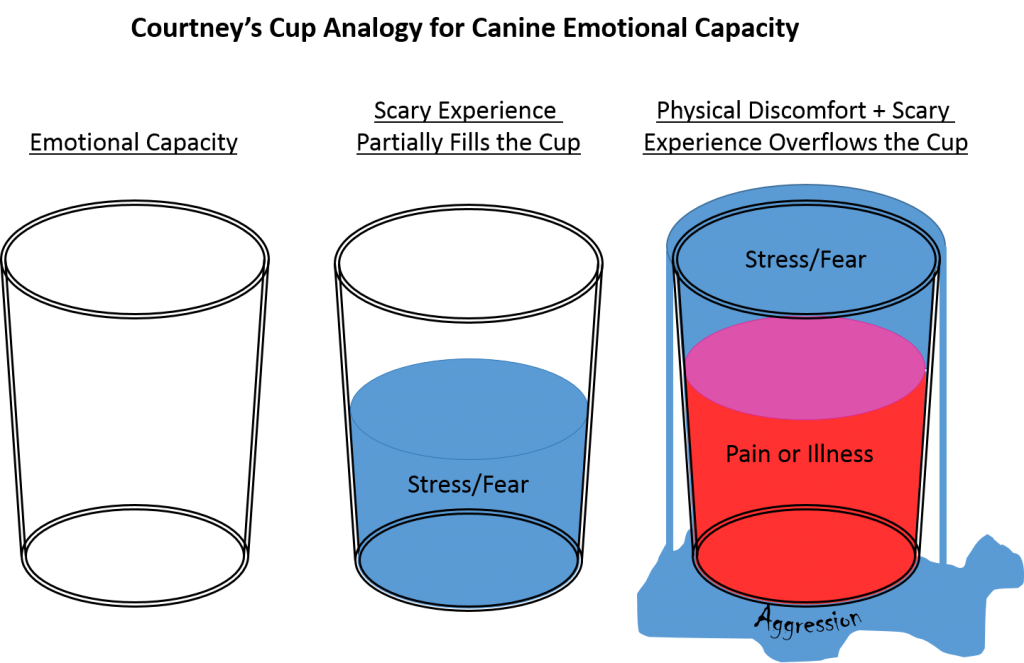

Think of your dog’s emotional capacity as a cup. Stress, fear, and other intense emotions will fill up your dog’s emotional capacity, their cup. Physical discomfort, like pain, nausea, and so forth, will also fill your dog’s cup. When the cup overflows, the result is frequently aggressive behavior (or other outward manifestations of extreme fear). Some dogs, like mine, have small cups, and training can help expand your dog’s emotional capacity. But sometimes, the dog has plenty of emotional capacity, it’s just that a lot of it is already being taken up by physical discomfort. In this way, physical discomfort decreases our dogs’ emotional capacity for dealing with other things that upset them.

I’ve always understood this on an intellectual level and the cup analogy has helped me conceptualize it. Recently, however, I have come to understand this on a very real and personal level.

You see, I have a few phobias of my own, but one in particular has been difficult since I moved to Denver. It gets triggered here a lot more than it did in New York, where I lived previously. You see, I am completely petrified of bees, wasps, and, really, anything with yellow stripes that looks like it might be able to sting me. It’s a visceral phobia that has regularly caused embarrassment since childhood, as I run away, ducking and dodging, arms flailing, etc. The impulse is strong, but in the two years since I moved to Denver I’ve been working on desensitizing myself to bees and wasps (there are plenty to practice with in my neighborhood) and my reactions to them have gotten a lot better. But! Over the last 2.5 months, I’ve been dealing with some health problems. I don’t want to get too into the details but let’s just say I’m experiencing my own physical discomfort. And it’s been giving me particular insight into the whole pain-fear connection.

I have put loads of effort into getting myself under control around bees and wasps and it has largely paid off, but on the days where I’m feeling my worst, all bets are off. Since my illness started a couple months ago, I’ve found that on the bad days I will get fixated on bees or wasps in my vicinity. If I hear a buzzing near me, I become hypervigilant, heart racing, scanning my surroundings. There has definitely been some jumping and running of late, which I have more or less managed to avoid doing for the past two years. I’ve taken to avoiding sections of our neighborhood that are particularly dense with flowers and plants that attract the dreaded yellow insects. All this has made it a lot harder to walk my dog, who has her own fear issues outside.

But it has also given me a new appreciation for what our animals must experience when they are not feeling their best. I am an intelligent, mostly rational human being, and even I find it alarmingly difficult to face my fears when I am physically unwell. Imagine how hard it must be for our dogs, who largely operate on instinct rather than intellect; they are reactionary rather than rational. While I know, intellectually, that bees are very unlikely to harm me and wasps will mostly leave me alone if I don’t provoke them, my fearful dog can’t rely on the same rationality to tell her that the screaming children nearby are not an existential threat. She can’t simply say to herself: “Self. Don’t worry about that motorcycle. It will be gone in a second.” Instead, she relies on me to demonstrate that everything will be alright and even that is not enough sometimes. When the triggers stack up or if she’s not feeling very well in the first place, her cup is going to overflow. She’s going to have a bad reaction, and this experience — recognizing my own susceptibility to amplified fear responses with physical discomfort — reminds me to be patient and compassionate with my dog when she cannot contain her own fearful reactions.

Finally, this experience has been a stark reminder of why good veterinary care is an important component of any program to address our pets’ behavioral health. Ruling out health problems and making sure we are providing appropriate and adequate nutritional support is a crucial first step in treatment of aggressive behavior.